Article by Thomas Stephan, climate consultant at Carbometrix

The digital world is powered by data, and the engines of this world - Artificial Intelligence (AI) and data centers - are rapidly expanding their capabilities. However, behind these notions of “digitalization” and “dematerialization” hides a significant physical infrastructure with rapidly escalating environmental and resource demands. The sector’s exponential trajectory in energy and material consumption now presents a critical challenge to global decarbonization objectives and the Paris Agreement alignment.

In this analysis, we explore the primary constraints imposed by digital sector demands and outlines strategic pathways to align the industry with a sustainable ecological transition.

Defining the infrastructure: AI, GenAI, and the data center landscape

For the past few years, the digital revolution has been synonymous with the rise of GenAI and its most famous Large Language Models (LLMs). But the infrastructures at the core of this revolution - data centers - have existed long before the advent of ChatGPT. And AI itself has existed, both in concept and in application, for a much longer time. So, a little clarification is in order.

Data centers have been the beating heart of the internet ever since its inception and democratization in the 2000’s. Their main function is to outsource data storage and processing, which allows their access by users at all time and the centralization of computation capabilities. Today, these servers cover a wide range of functions : data storage, video streaming, cloud gaming, social networks, and of course AI.

AI, in fact, predates even the internet. The term artificial intelligence was first coined in the 1950’s to describe this newly appearing field of algorithmic studies. Since the 2000’s, AI has been mostly focused on machine learning, which are programs that can improve their performance on a given task automatically.

But the real revolution came with a subset of machine learning called deep learning. This technique makes use of what are called artificial neural networks, inspired by the functioning of our own brains, that vastly expands the capabilities of AI and makes it proficient at a wide variety of tasks. This is the technique that gave rise to Large Language Models, or LLMs, that we know today. This new wave of Generative AI (GenAI), propelled by models such as ChatGPT, has rapidly entered the commercial mainstream, often becoming the de facto public definition of AI.

The rapid scaling of these models is evident: LLM size has increased 10,000-fold in five years, driving adoption to 400 million weekly users for models like ChatGPT by early 2025. Today, more than 40% of companies use GenAI and the total market for GenAI is expected to exceed 1 trillion dollars by 2032.

As of now, GenAI still only represents around 15% of the total usage of datacenters around the world, which are still mostly reserved for traditional uses. The growing size and performance of models, as well as their still expanding applications, could bring this figure up to 55% by 2030. Such a lightning rise increasingly calls into question the sustainability of the whole enterprise, as data centers are a very energy intensive infrastructure.

Hungry hungry servers - The strategic implications of the digital sector’s growing appetite

Accurate estimation of generative AI's energy consumption remains challenging. Information is scarce, and the key industry players maintain jealous secrecy, not to say organized opacity, about the performance and power consumption of their models.

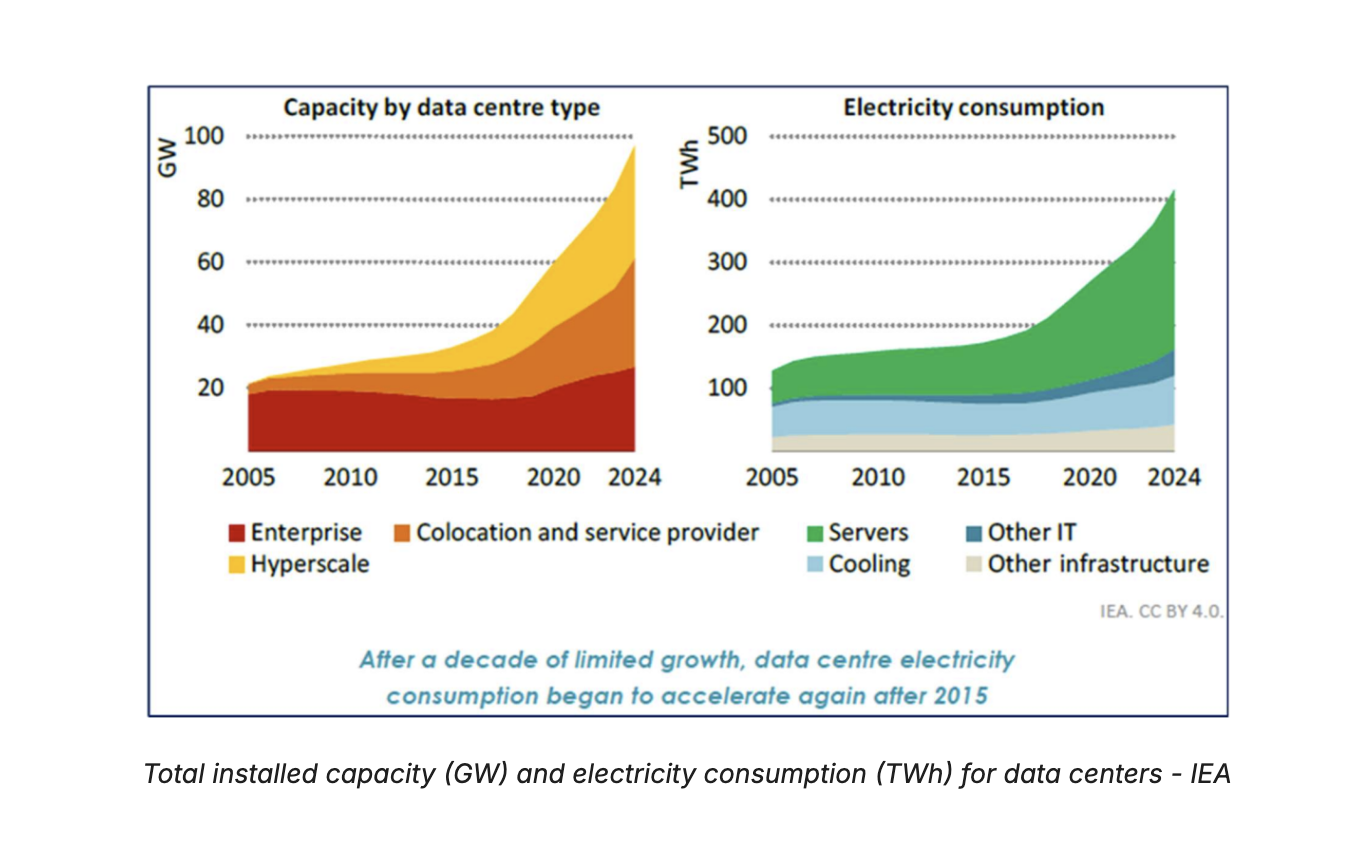

Assessing the future energy consumption of the digital world thus requires a focus on data centers, the central power and processing hubs of the entire infrastructure. In 2024, data centers represented 1.5% of the world’s electricity consumption, or 415 TWh. This consumption has already rapidly accelerated in recent times, with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 13% over the past 5 years.

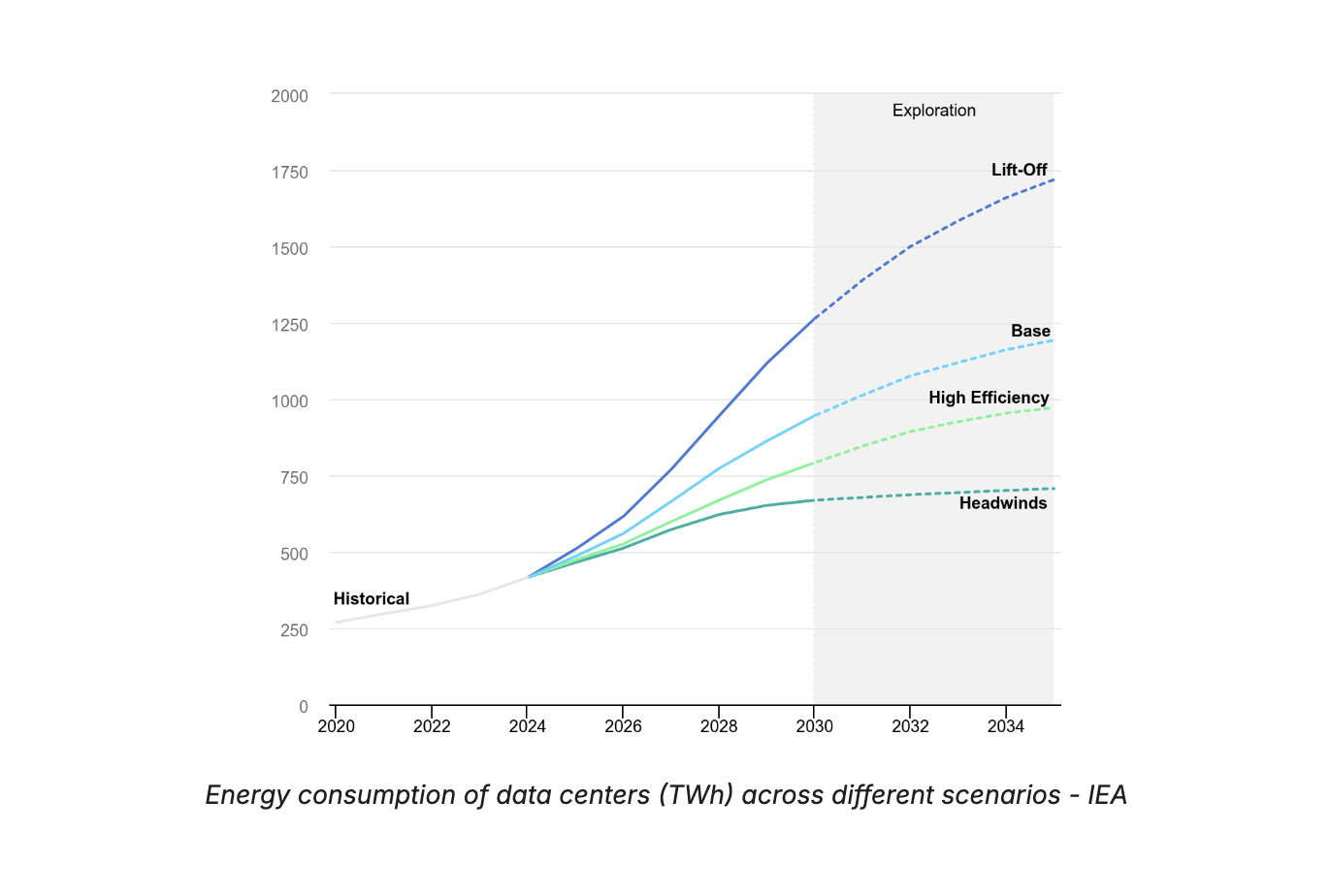

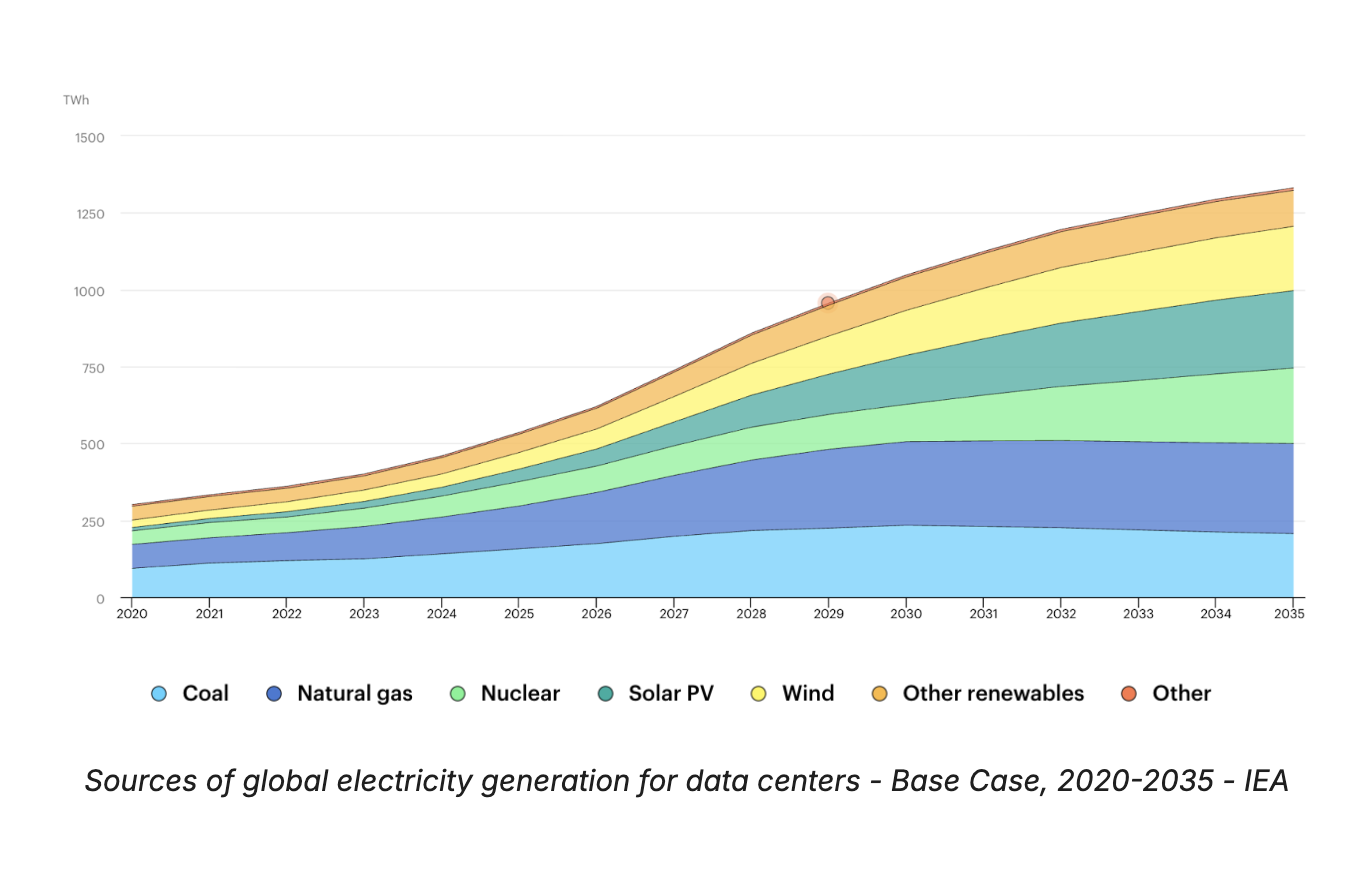

These trends do not show any sign of slowing down. With the exponential growth of GenAI, more and more investments in larger and larger data centers are being made. Sector-wide energy consumption is projected to increase by at least 50% by 2030, with extreme-case scenarios indicating a potential four-fold increase by 2035.

In a world where electrification of uses remains a critical challenge of the ecological transition, these increasingly power-intensive infrastructures risk creating significant pressure on electrical grids, potentially competing with the electrification requirements of other key industries.

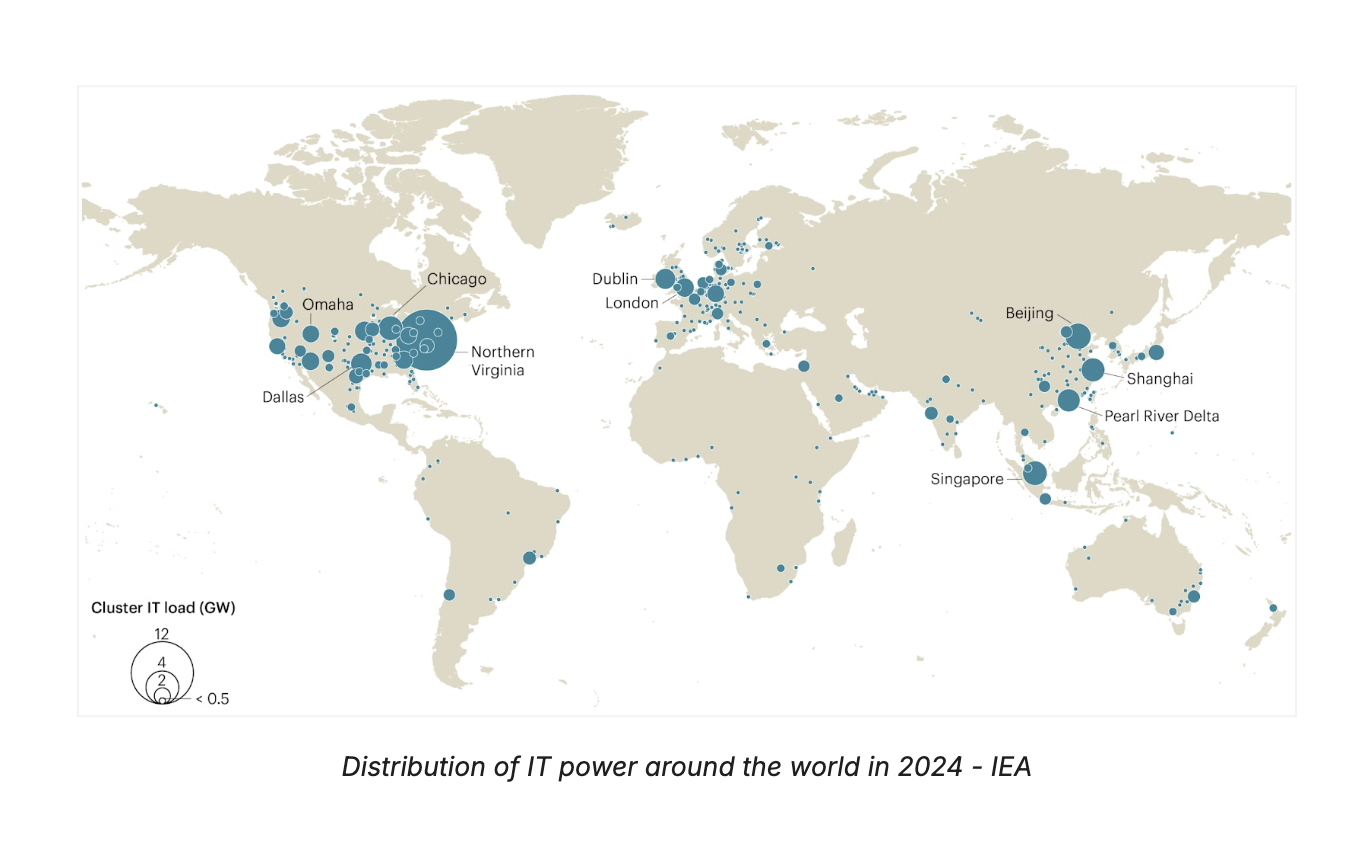

The uneven global distribution of data centers across different regions and countries further exacerbates these impacts locally. Their concentration in certain areas (Virginia in the US, Ireland in Europe) brings rising tensions within local networks. In Ireland for example, data centers now represent more than 21% of the country’s total electricity consumption, surpassing residential housing. In Virginia, this figure increases to more than 25%.

With around 8,000 total datacenters around the world in 2024 and hundreds more planned for the coming years, concerns about the ability of local electricity production to meet the needs of these new facilities are increasing. Since 2021, Dublin has enforced a moratorium on requests for new data centers - this action followed the national grid operator's announcement that it lacked the necessary capacity and availability of renewable energy to supply any further installations in the area.

The digital footprint: How energy demand challenges decarbonization

This ever-increasing energy demand is not only an economic consideration - energy costs typically represent between 30 and 60% of the total OPEX - it is also increasingly becoming an environmental concern.

The IEA estimates the electricity generation for data centers represents 180 MtCO2e direct GHG emissions, or 0.5% of the global total, with it potentially rising to up to 1.5% in 2035 in the most extreme demand scenarios. Problematically, this only partially captures the full scope of emissions, as it omits significant material sources like embodied carbon, upstream electricity emissions, and backup power sources, which can constitute a large portion of the overall emissions.

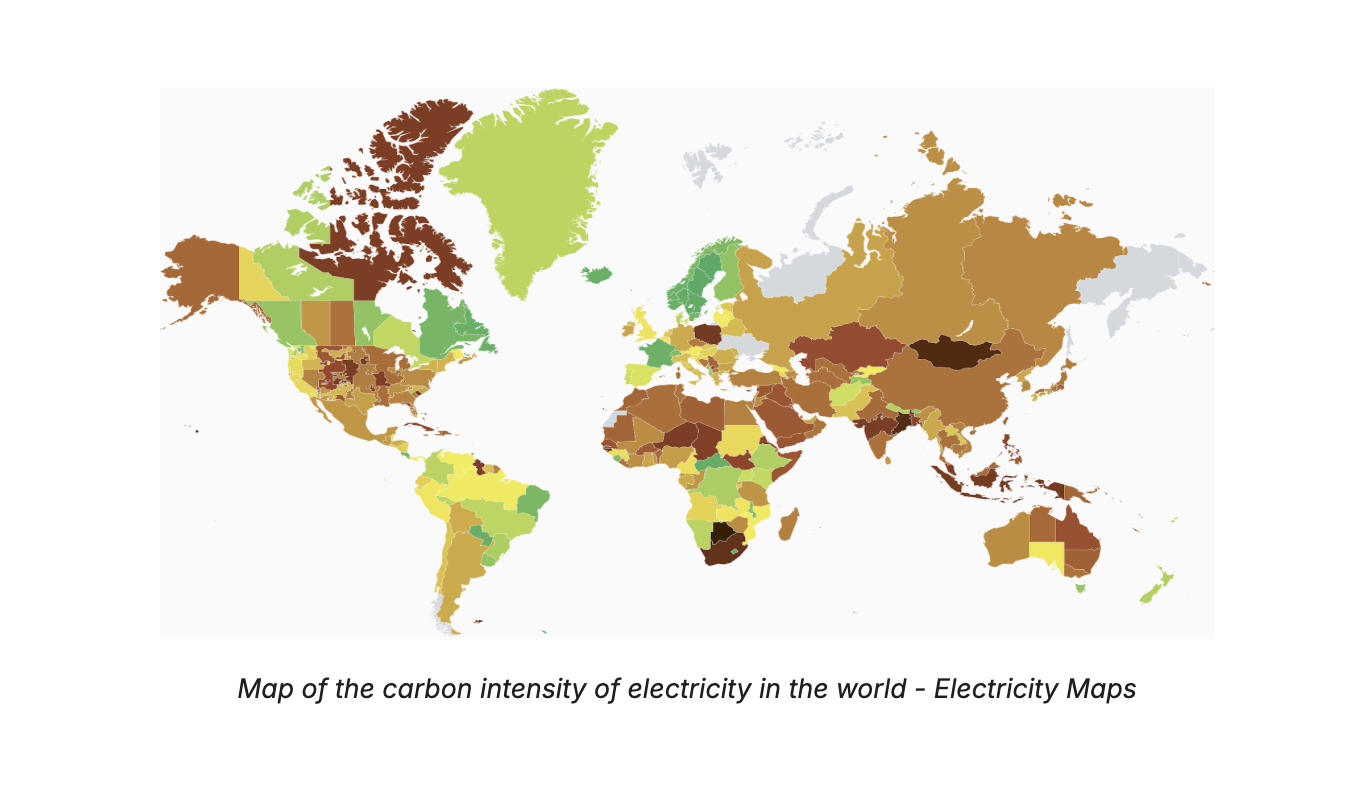

A key component of the issue arises from data center location often being determined by economic and regulatory arbitrage, leading to deployments in regions where electricity production still relies heavily on fossil fuels. Average carbon intensity of electricity provided to facilities thus remains high and shows no sign of decreasing before 2030 at best.

As we can see, fossil fuels are expected to remain the dominant source of electricity generation for at least the next 5 years. Countries like the US and China, which together represent 70% of the global data center electricity consumption, still mostly rely on fossil gas and coal respectively for the powering of their facilities. In addition, as this growing demand puts pressure on the grids, regional or national operators are delaying the closing of emissive power plants in order to provide the necessary power. Three coal plants in Mississippi and Georgia with a combined power of 8.2 GW have seen their retirement pushed back by sometimes over a decade to meet the increasing energy demands.

The emerging reliance on dedicated, new fossil fuel generation for data centers also could present a clear stranded asset risk. For instance, the Global Energy Monitor identified 44 GW of new gas-powered projects (37 GW in the US) planned exclusively to meet this demand. Other facilities also resort to off-the-grid electricity production, such as the new “Colossus” data center opened by Elon Musk’s xAI in Memphis, which uses 15 gas turbines to supply its energy locally.

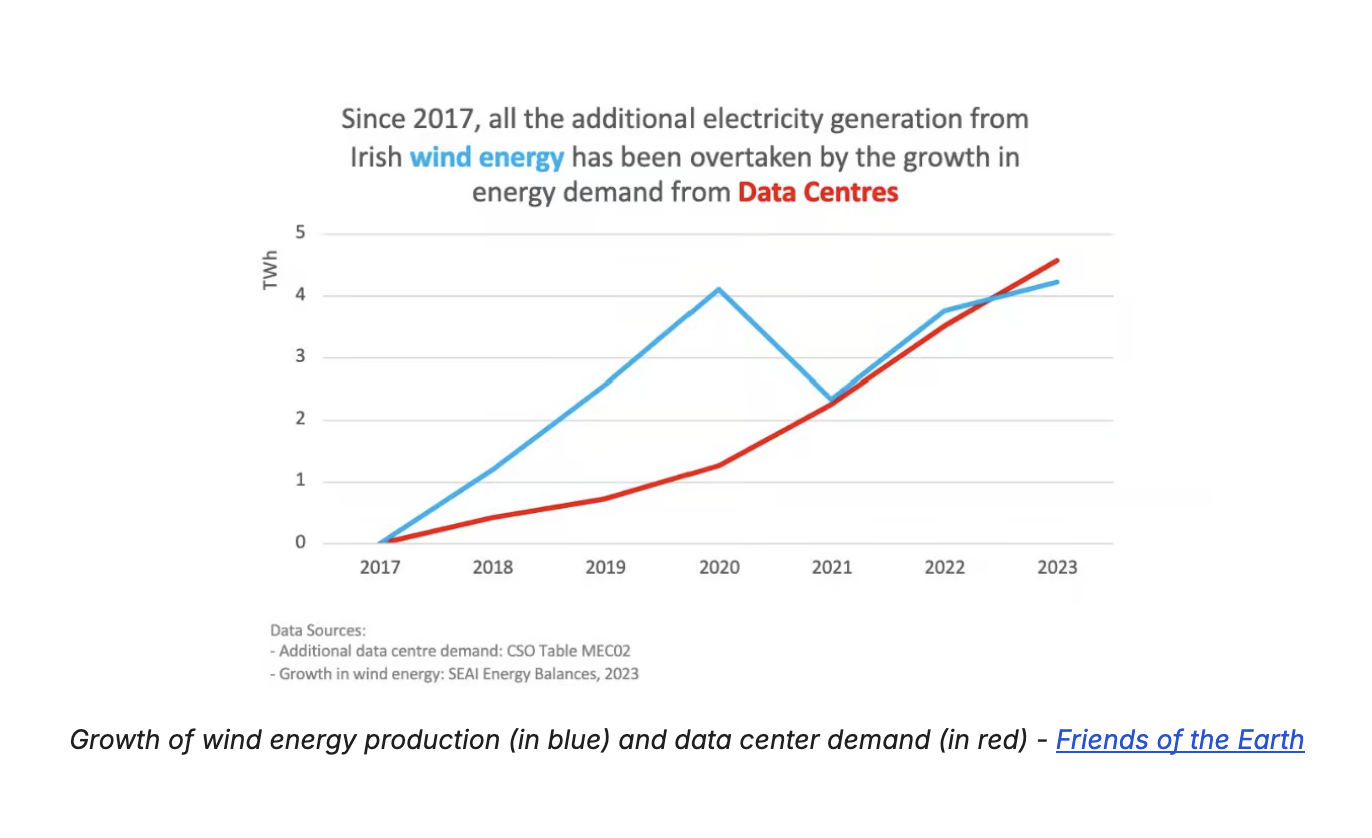

The pace at which demand is growing makes decarbonizing this energy supply a difficult task. The installation of new renewable energies struggles to keep up with the new demands, making substitution with cleaner electricity often impossible. In Ireland for instance, additional electricity generation from wind energy has been overtaken by the growth of data center demand.

The burgeoning energy demands of data centers and the AI sector thus poses a significant and escalating challenge to global decarbonization efforts. The continued reliance on fossil fuels, driven by economic siting and the sheer pace of demand growth, and even the development of new, dedicated fossil fuel infrastructure induces clear physical and financial risks. Until the growth rate of clean energy generation can outpace the soaring demand from the digital world, the sector will continue to exert considerable pressure on the world's energy grids and its climate goals.

Beyond operations: The challenge of embodied carbon

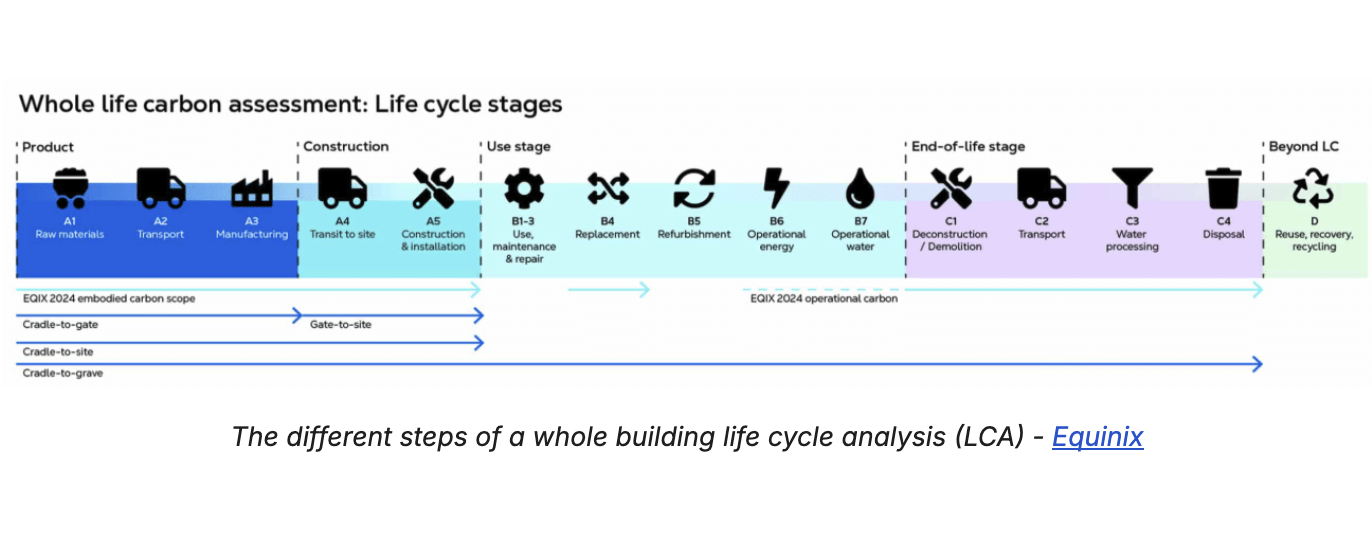

We have, until now, only tackled the topic of emissions related to the electricity consumption of data centers. However, operational emissions only represent a fraction of the total lifetime emissions of such infrastructures, while the remaining share is composed of embodied emissions. This category regroups all the emissions happening at the construction stage of the data center :

Superstructure and masonry

Mechanical, electrical, power and cooling equipment

IT equipment

Uninterrupted Power Supply (UPS) and battery storage

Etc.

Embodied emissions represent a critical, often underestimated component of the total lifecycle footprint, with current analysis predominantly focused on operational energy demands. Embodied emissions currently represent 20 to 30% of the total lifecycle emissions of a data center with the current carbon intensity of electricity used in operations. Even with a completely decarbonized energy supply, embodied emissions from data centers would thus remain substantial, potentially reaching 100 to 150 MtCO2e by 2035. For comparison, this constitutes 33 to 50% of the United Kingdom's current total carbon footprint.

Addressing embodied carbon is thus crucial to a successful decarbonization of the industry. A Shift Project's analysis in France suggests that, on top of heavy decarbonization of the electricity mix, achieving Net-Zero compatibility will require a difficult reduction in the share of embodied emissions to just 5% of the total, if global consumption rises to the estimated 1,000 TWh.

As is the case with energy consumption, the topic of GHG emissions does not give us the full picture and the need for large quantities of highly specific materials also presents additional risks. The value chain of materials used in AI infrastructure relies on precious metals to produce the necessary wafers, chips and processors, whose production is heavily concentrated in the hands of a couple actors with a monopolistic position (TSMC, NVIDIA).

The industry thus faces a serie of environmental, social, and supply chain risks that arise from the extraction and production of the necessary materials used in data center construction. Acting on reducing embodied emissions is not simply a way to reduce one’s carbon footprint, but should take part in a broader reflection on how to minimize negative externalities linked to the global supply chain, thus minimizing the exposure to risks associated with such impacts.

From GenAI to GreenAI: A framework for sustainable digital deployment

With current trends, the carbon footprint of data centers and AI seems poised to follow their exponential growth in the coming years. But these rising emissions are not inevitable, as there are ways to minimize the footprint of digitalization and make the AI revolution more sustainable, whatever your place in the value chain may be. We identify three strategic pillars to enhance sustainability and de-risk digital investments.

Minimize energy-related emissions

As detailed in this article, the substantial electricity requirements of data centers and their consistently high carbon intensity constitute an increasing concern and currently account for the majority of emissions associated with these infrastructures. Addressing operational emissions should thus be the first priority, by acting on both sides of the equation through sobriety and decarbonization.

Sobriety measures aim mostly at increasing the efficiency of data centers, i.e. the amount of energy required to perform the same amount of tasks. This can be done directly via hardware improvement, with the use of chips dedicated to AI for instance, and the optimization of data centers Power Usage Effectiveness. On the software side, different technologies are emerging to optimize the performance of AI models and thus reduce the power needed to process a request. Architectures like the Mixture of Experts (MoE) for example can avoid mobilizing the entirety of the model at once thus reducing the required energy.

Decarbonization measures focus on reducing the carbon intensity of the electricity consumed by the data center. The location is critical, with the focus on countries or regions where electricity production is mostly low-carbon. Strategic siting in low-carbon grids - ie. France over Germany - can immediately reduce electricity-related emissions by over 90%. Additionally, local renewable energy production is a great way to further decarbonize the electricity consumed, with solar panels or geothermal energy providing direct access to zero-emissions power sources.

Other operational emission sources should also be addressed, in particular the use of refrigerant fluids within the cooling systems of the datacenters. These fluids, while generally present in small quantities, have considerable Global Warming Power (GWP) meaning that a small quantity leaking into the atmosphere can result in consequent GHG emissions. To limit these emissions, which can represent up to 5% of the total operational footprint, solutions already exist :

High GWP refrigerant gases like R32 or R410a can be substituted with much less impactful gases like R290 (propane) or R1234-ze which have negligible GWPs

Solutions without refrigerant gases also exist, like adiabatic cooling units which allow to bypass this problem entirely in the right circumstances.

Tackle embodied carbon

As we have observed, the more the energy supplied to a data center becomes decarbonized, the greater the proportion of its embodied emissions within its lifecycle. Reducing this early-stage carbon impact should be part of any comprehensive decarbonization strategy. Companies like Equinix are now embracing a holistic approach by aiming to reduce emissions across data centers lifecycle stages. This approach can be broken down as follows :

Measure emissions ahead of time by using the whole building lifecycle analysis (WBLCA) to clearly pinpoint emissions hotspots

Avoid using new materials whenever possible, by exploring design options that use less resources and reusing or repurposing materials

Reduce the embodied carbon in the remaining materials, by favoring low-carbon alternatives like recycled steel of low-carbon concrete.

Focus on key uses with positive externalities

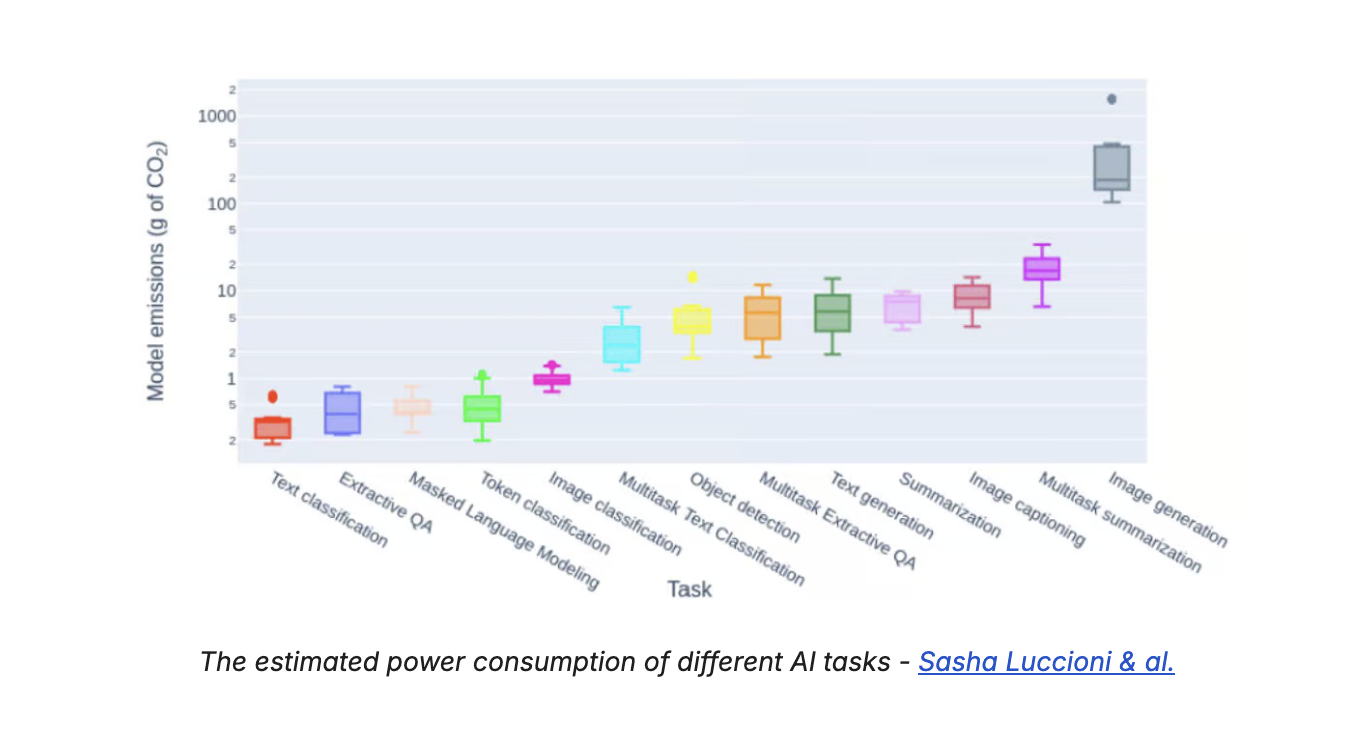

AI is an umbrella term that regroups a wide variety of algorithms used in many different applications. The utility of these applications is not uniform. While some contribute to value creation processes, others offer minimal added benefit. Furthermore, their energy consumption does not correlate proportionally with their usefulness : text analysis and summarization can provide extensive value and efficiency gains with relatively low energy demands, while conversely image and video generation require significantly more energy and are for now mostly constrained to recreational uses.

To go one step further, some applications related to AI may even provide optimizations in other sectors, directly or indirectly reducing their induced emissions. Potential has already been identified for a few key activities :

Power generation

Transport

Industry energy consumption

Buildings energy consumption

Depending on the adoption and efficacy of these applications, the IEA estimates that the total reduction of direct and indirect emissions across all sectors could reach up to 1,400 MtCO2e in their most optimistic scenario. While this figure is very hypothetical, and rebound effects need to be taken into account, focusing on the provision of such tailored solutions constitutes a key element in ensuring the compatibility of advancing Artificial Intelligence with a sustainable global framework.

Conclusion

Despite appearances, the rise of the digital world has had a very physical impact on our infrastructure and its energy consumption. This has been now compounded by the rise of GenAI, which has seen the predictions for the sector's future electricity needs skyrocket. The question of alignment with global emissions targets is now critical, as data center energy consumption is forecasted to exceed 5% of the global total, exacerbating grid pressure and competition for clean power.

Furthermore, the question of their carbon footprint is not the only environmental concern arising from the exponential growth of AI. Other externalities such as the pressure put on local power generation and electricity grids and the reliance on overloaded supply chains all need to be taken into consideration when assessing the footprint of the digital world.

There are clearly identified levers to make these coming developments more sustainable and reap the benefits of the AI revolution without sacrificing our environmental commitments. Focusing our efforts on reducing emissions across the entire lifecycles of our data centers - from embodied carbon to operation emissions - while focusing only on key and beneficial uses of AI should now be the priority.

The next phase of infrastructure development is determinative. Acting now is essential for integrating the digital revolution with material environmental commitments. Outside of purely environmental concerns, it is above all a crucial risk-management topic that needs to inform value-creation efforts.

Bibliography :